On 15 September 2022, about 100 participants, comprising past and present MSE family staff, and partners from the people, private and public sectors, gathered to plant 50 trees in commemoration of the ministry’s Golden Jubilee. Credit: Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE)

Singapore reflected on its journey towards a green and resource resilient nation in September, as the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE) celebrated its 50th anniversary.

The commemoration was especially poignant, as it occurs in a year where Singapore keenly felt the effects of climate change and geopolitical tensions on the country’s food supply.

To ease the impact of such supply disruptions, Singapore has been building the agri-food industry’s capability and capacity to produce more with less, sustainably.

Despite such ambitious plans, a quick survey of Singapore’s recent past reminds us that equally dramatic transformations have been accomplished before, though they involved significant costs and sacrifices.

Similarly, as Singapore undertakes another agricultural transformation in the years ahead, potential trade-offs and costs will need to be understood, managed, and accepted.

Evolution of Singapore's Agri-food Industry

For decades, change has been the only constant for Singapore’s agri-food industry.

When Singapore attained self-governance in 1959, many of the island’s 20,000 farms employed relatively inefficient and labour-intensive production methods. As such, the newly formed Primary Production Department (PPD) sought to boost local food production by increasing the knowledge base of farmers, and encouraging them to adopt more efficient farming techniques and tools.

For instance, to increase the output of vegetable farms, night classes and lectures were conducted to introduce farmers to newer farming practices and technologies.

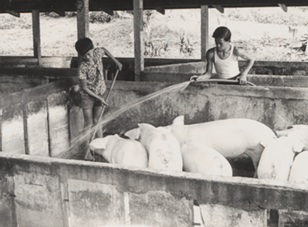

The PPD also opened “extension centres” throughout rural Singapore, providing free vaccination services, veterinary support, and technical advice to pig and poultry farmers.

Such efforts quickly began to reap fruit. By the late 1960s, Singapore was effectively self-sufficient in eggs, pork, and poultry.

As the 1970s dawned, Singapore’s extensive urbanisation and industrialisation resulted in a significant drop in available farmland, from about 14,000 hectares to about 8,400 hectares. The country needed a new way to produce more food on less land.

To meet this challenge, the PPD transformed Singapore’s agricultural sector. Larger farms using more intensive production methods were introduced. Small-scale, subsistence farms were phased out, or encouraged to merge with other small farms.

As Singapore created more reservoirs to improve its water security, many pig farms along these water bodies had to be resettled, to prevent toxic pig waste from polluting these water catchment zones.

Dedicated farming estates in Punggol and Jalan Kayu were created to house these farms. Such estates had the additional benefit of allowing resources like water, electricity, and veterinary services to be shared more efficiently between farmers.

These significant transformations allowed Singapore to grow more food with less land. By 1977, the PPD declared that Singapore was “self-sufficient in pigs and poultry”. Even with reduced land area, local farms could now produce over 1.2 million pigs, 27 million chickens, and 508 million hen eggs annually.

In the 1980s, as farmland in Singapore continued to shrink, further trade-offs in Singapore’s agricultural sector had to be made, even as more efficient food production technologies were explored.

In 1984, the government announced that pig farming would be completely phased out due to the high environmental and financial costs of maintaining such local production. Singapore would eventually import all its pork from a diverse range of regional and international sources.

At the same time, the PPD began experimenting with advanced agricultural technology, or ‘agrotech’ to further boost food production with less land and labour.

Agrotechnology parks were established in locations like Lim Chu Kang, Mandai, and Loyang. High-tech prawn and fish farms were also gradually developed to meet the local demand for seafood.

Of Change...

Our agri-food industry has come a long way since 1959. Despite food farms occupying only about 1 per cent of the island’s total land use, the industry has continuously evolved and transformed to supplement the nation’s food needs.

However, these transformations also required sacrifices and trade-offs. For example, farming communities had to be uprooted and resettled away from Singapore’s water catchment areas in the 1970s to safeguard Singapore’s water security. When pig farming was phased out in 1984, older, traditional ways of life had to be given up, and farmers had to find new livelihoods.

Today, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), the PPD’s direct successor, continues to help farmers increase their food production capability and capacity. Like the PPD once did, SFA today works with the industry to innovate and modernise various aspects of local food production.

For instance, to support the industry’s transformation into a highly productive and resource-efficient sector, SFA provides funding support and research grants into fields like sustainable urban food production.

To develop a pipeline of talent for the industry, the Agency is nurturing a new generation of farmers skilled in agricultural and aquacultural sciences, engineering, and infocomm technology, through collaborative ventures with educational institutions.

Moreover, to optimise agricultural land, SFA is developing the Lim Chu Kang area into Singapore’s core agri-food production hub. Aquaculture policies were also reviewed earlier this year to provide the industry with greater certainty on their sea space tenure, allowing them to make longer term capital investments.

Such initiatives will continue apace as SFA works towards its vision of a productive, resource efficient and climate resilient agri-food industry.

...and Challenges

As we have seen, however, there will inevitably be difficulties ahead: whether in terms of giving up land to allow for holistic planning and optimising of agricultural spaces; preserving our heritage while adopting new innovations and technologies; or other as-yet-unforeseen challenges.

Though SFA has taken steps to mitigate the impact of these coming transformations, such as by working closely with stakeholders on designing the Lim Chu Kang future agri-food hub, setbacks will inevitably be encountered as policymakers and farmers experiment with new methods, systems, and technologies. All parties will need to be mentally prepared for failures, missteps, and sacrifices in the process of turning our agri-food sector into a productive, resource efficient and climate resilient one.

The Road Ahead

As the climate changes and geopolitical situations evolve, innovation and transformation will remain necessary aspects of sustaining Singapore’s food security. Singaporeans – whether they are policymakers, producers, or ordinary citizens - will likewise be challenged to reimagine how and where we grow and get our food from. There will almost unavoidably be challenges to confront, compromises to be made.

Hence, even as we celebrate MSE’s 50th anniversary and our accomplishments thus far in building a green and resource resilient city, it might also be useful to reflect on the costs and sacrifices that were made along the way.

Doing so will allow us to be better prepared to understand, manage, and accept change and challenges in the coming years, as Singapore transforms itself again to better feed the nation.

About the Author

Choo Ruizhi is a Senior Analyst in the National Security Studies Programme (NSSP) at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is interested in the environmental histories of Southeast Asia in the twentieth century, and is currently exploring the histories of agricultural animals in newly independent Singapore