Beyond causing fish deaths, algal blooms resulting from climate change are also a source of phycotoxins that can cause serious health conditions when the toxins find their way into seafood consumed by humans.

The conversation on climate change is getting louder and more urgent. If there is one thing to take away from the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow held in November 2021, it may be that this has become the most critical decade for mankind to take action to arrest the rise in global temperature. Through human activities such as deforestation and fossil fuels burning, greenhouse gas concentrations are at their highest levels in 2 million years. According to the United Nations, the Earth is now about 1.1°C warmer than it was in the late 1800s, with the last decade being the warmest on record.

The consequences of climate change on the global ecosystem have been far-reaching. We are already witnessing its effects – melting glaciers, rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, ocean warming and acidification, and extreme weather events.

An impending food security crisis

The link between climate change and food supply has been well-documented by various scientific studies and international organisations. Climate changes are expected to affect critical components of the world’s agricultural and food production sector, such as crops, livestock and seafood.

For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has highlighted the impact of rising temperatures on declining crop yield and suitability. These may have downstream effects on pasture and feed quality, affecting livestock health and viability.

Our oceans too, are not spared from the effects of climate change. In December 2021, more than 1,700 tonnes of fish died in West Sumatra’s Lake Maninjau, in part due to extreme weather such as strong winds and heavy rains. Absorption of carbon dioxide has also made oceans warmer and more acidic. This lowers their capacity to absorb and store oxygen, as well as accelerates massive algal blooms, threatening the survival of marine life and supply of seafood.

More recently, in January 2022, warmer and drier weather led to the destruction of crops in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. This led to shortages in vegetables in the region, which had earlier been hit by excessive rains and floods. These examples illustrate the need to transform farming so that it can be productive, climate-resilient, and sustainable for the future.

The effect of climate change on food safety, while equally important, has arguably been less talked about. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in 2020 reported that climate change also creates conditions that threaten the safety of our food. Changes in climate conditions can introduce new and emerging harmful compounds during the food production and distribution process, causing food safety risks and exposing consumers to potential health issues.

To appreciate the potential scale of the problem, let’s look at the existing global food contamination situation. FAO reports that presently 14% of food worldwide does not reach consumers due to food contamination issues. Foodborne hazards such as mycotoxin contamination – fungal infections commonly found in staple crops – affect 600 million people each year, causing nearly half a million deaths and leaving behind long-term health issues such as kidney and liver damage, development stunting in children, cancer, and other illnesses.

With climate change, more food contamination issues caused by such foodborne hazards are projected to arise.

How does climate change introduce food safety hazards into our food system?

Firstly, climate change could increase the growth, proliferation and duration of algal blooms. These algal blooms not only decimate wild and farmed fish stocks, but they are also a source of phycotoxins that find their way to seafood and shellfish consumed by humans. Phycotoxins can result in a host of serious health conditions, including respiratory problems and liver and kidney damage.

Secondly, heavy metals may accumulate in food and drinking water arising from changes in climate conditions. Intense rainfall can displace heavy metals from the soil and wash them into community water systems and the sea, and into our food chain. This can have an adverse impact on human health and marine ecosystems. At the same time, rising soil temperatures can lead to increased uptake of heavy metals by plants. For example, rice is known to absorb heavy metals like arsenic from the soil, which accumulates in the grain eaten by millions of people. Consumption of excessive amounts of such heavy metals over a prolonged period of time can lead to cancer, and respiratory and immunological damage.

Thirdly, climate change is expected to change the geographic distribution and life cycles of agricultural pests globally. This could result in an increase in the levels of pesticide residues on crops as farmers turn up their use of pesticides to protect their crops. Excessive dietary exposure to pesticides can lead to health problems such as endocrine issues, reproductive disorders, cancer, and damage to the nervous system.

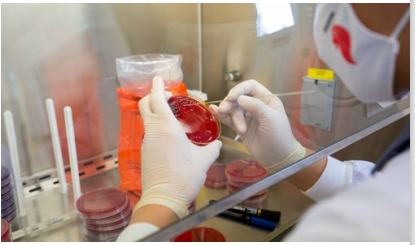

Fourthly, there is growing evidence that environmental changes induced by climate variations will result in more foodborne diseases. New foodborne pathogens may emerge, leading to more foodborne illness outbreaks. Warmer environments and wetter weather create ideal environments for pathogens such as Salmonella and Campylobacter, as well as pathogen-carrying insects like flies and cockroaches, to breed and survive for longer periods. Locally, we have already encountered severe foodborne pathogen outbreaks with life-threatening consequences. For example, Salmonella was found to be behind a mass food poisoning incident caused by a food caterer in 2018, where 63 people fell ill and one person died. In fact, the WHO has reported in 2017 that cases of salmonellosis can increase by 5-10% for each 1⁰C increase in weekly temperature beyond an ambient temperature of 5⁰C. With changes in the climate, the rising threats posed by foodborne pathogens will continue to pose food safety challenges.

Responding to climate-induced food risks requires a coordinated and systematic strategy. To better manage new, emerging and unexpected foodborne risks, new and cutting-edge technologies need to be effectively adopted and integrated with food safety science. And when such food hazards are identified, mitigation response should be prompt, efficient and effective.

To this end, SFA has adopted three key strategies to stay ahead of these challenges.

The first is to leverage data to anticipate new, emerging and unexpected foodborne risks. Such information would include global food notification alerts, food poisoning reports from hospitals and other community-based sources, consumer feedback or complaints, and inspection data. For instance, descriptive and text analytics are utilised to make sense of information picked up through horizon scanning, giving SFA a head start on any emerging food hazards in our market. This allows resources to be prioritised for more targeted risk management and communication.

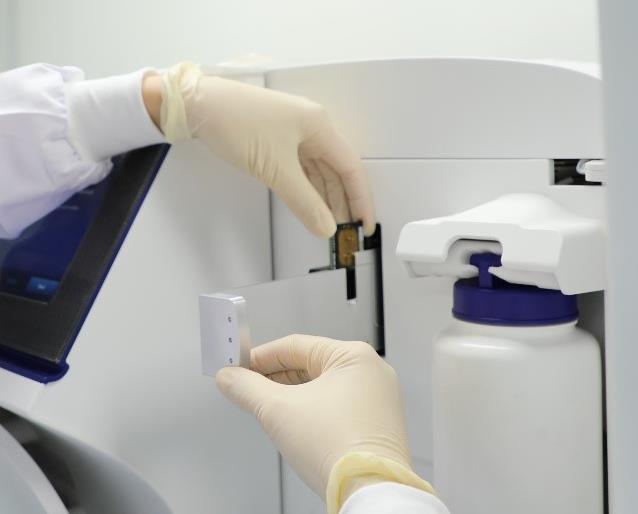

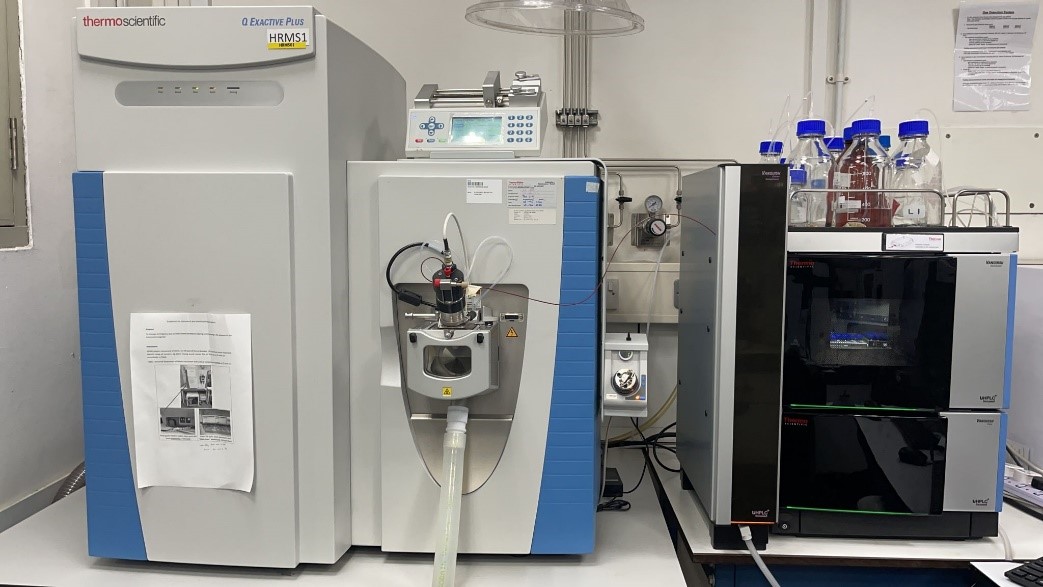

SFA’s second strategy is to develop capabilities to screen and study new, emerging and unexpected food safety hazards. Cutting-edge techniques such as next-generation genome sequencing are being used to fingerprint the DNA of microbial foodborne bacteria, allowing them to be identified and tracked. We are also developing capabilities to identify unknown or new emerging microbiological agents.

In Singapore, a “One Health” approach is adopted to combat foodborne hazards. These hazards include new and emerging food safety risks resulting from climate change. Made up of various public service agencies, academic and healthcare institutions, as well as the private sector, the One-Health network national surveillance programme allows for information and insights, capabilities, and technological expertise to be shared across agencies – to ensure the safety of our food.

Beyond the government and the industry, consumers too, can play a part in ensuring food safety. This includes equipping themselves with knowledge of food safety risks, and adopting good food safety practices. Together, we can safeguard food safety, even in the face of climate change.

About the author: Johnny Yeung is a scientist at the National Centre for Food Science, Singapore Food Agency. He conducts food safety risk assessments to determine the public health significance of food safety hazards to support SFA’s operations, and to facilitate pre-market regulatory approvals of novel foods.